Research

Rapid evolution and species coexistence under changing selective pressures: Microbes compete for resources, consume one another, and form symbioses, just like the myriad of fantastic organisms that form iconic communities visible to the naked eye (e.g., coral reefs and rainforests). These biological interactions alter the survival and reproduction of individuals, resulting in the coexistence or exclusion of different microbial species from an ecosystem. However, interactions between species are not static. They change with the environment (e.g., shifts in nutrient availability, toxicity, new competitors), as is increasingly recognized by community ecologists studying macroorganisms. Microbial communities, in particular, are unique in that they are often subjected to dramatic environmental shifts (e.g., high dosages of antibiotics to treat a disease), and individuals can readily evolve new or altered traits that can rapidly sweep through populations due to high rates of mutation and staggeringly large numbers of individuals (efficacious selection).

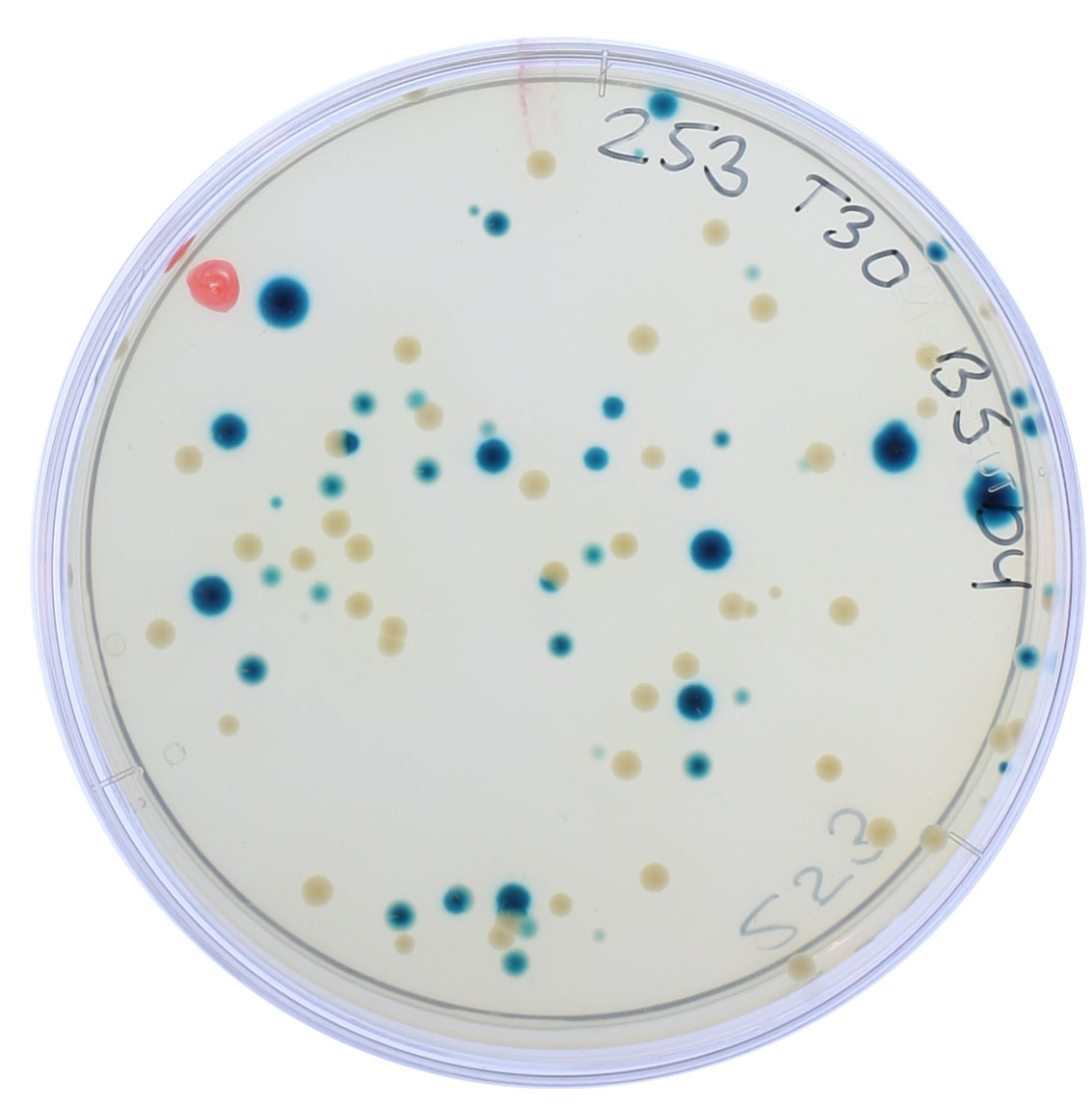

Significant effort has been dedicated to understanding microbial interactions in stable, idealized environments while often overlooking environmental fluctuations and the potential for evolution. To push the boundaries of that knowledge, we need a more detailed conceptualization of microbial ecosystems, one that integrates species interactions, the environment, and evolution. Through the study of small synthetic microbial ecosystems, we are currently unraveling the impact of antibiotics on species interaction networks and how this may be influenced by the evolution of antimicrobial resistance, a critical global health issue.

Host microbiome interactions and community assembly: Plants host beneficial, commensal, and pathogenic microbes. Much of what is known about plant microbiome interactions comes from our understanding of pairwise interactions between a host and pathogens/mutualists under optimal conditions. However, the host microbiota's final composition and community-integrated traits (e.g., harmful or beneficial to the host) are not necessarily a simple linear function of the constituent microbial species. Thus, predicting the final trait configuration and functional outcomes of host-associated communities may become increasingly challenging as microbial diversity changes and abiotic conditions become less favorable.

We are working with the model aquatic plant, Lemna minor, and its associated microbiota to understand how community-integrated traits and ecological function arise during the microbiome assembly process. We are particularly interested in the context-dependence of this process and how global change can modulate biological interactions between the host and its microbiota. This knowledge will be essential if we are to anticipate and mitigate the forthcoming consequences of global change on critical ecosystem services provided by plants.

Predator/prey trophic interactions in microbial ecosystems: Microbes form the base of aquatic and terrestrial food webs. Bacteria, in particular, are important prey items for microfaunal predators such as single-celled protists and nematode worms (e.g., Caenorhabditis elegans, shown in the adjacent picture), the activities of which ensure soil fertility and ecosystem function. However, little is currently understood about how predation modulates microbial community composition and function and how this may, in turn, impact key ecosystem processes or community-level traits.

We use microfaunal predators (primarily C. elegans) to understand how top-down controls regulate bacterial density, bacterial community composition, and the reciprocal arms-race evolution between predator and prey. In particular, we are interested in how predators influence important community-level microbiome traits. Because antibiotics are widely used in agriculture and livestock are an important reservoir of human pathogens, we are interested in how predators control the distribution of bacterial traits such as virulence and antimicrobial resistance in human impacted terrestrial and aquatic microbiomes.

Microbial biogeochemistry: Matter and energy are neither created nor destroyed but continuously transition through different forms. Microscopic unicellular organisms (bacteria, archaea, protists) are Earth's most ancient and ubiquitous life forms, and their collective activities and metabolisms direct this energy and matter through the closed Earth system, driving biogeochemical cycles and making life as we know it possible. Our team works to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying different microbial metabolisms, the distribution of these metabolic processes in the environment, and the implications of these processes for the fluxes of matter and energy at a planetary scale.

Many environmentally relevant microbes have yet to be cultured, and those that have can be very challenging to grow in the lab. To partially circumvent this challenge, we use DNA sequencing and computational approaches to study microbial genomes obtained directly from the environment. Using the information encoded in DNA, we aim to identify selective pressures driving the evolution of gene content variation between natural microbial populations, uncover novel metabolic potential encoded within microbial communities, and ultimately link these patterns to biogeochemical processes. Our prior work in this area has focused on microbes from the oligotrophic surface ocean, e.g., Prochlorococcus (the most abundant photosynthetic cell) and SAR11 (the most abundant organism in the sea and possibly the planet).